The mayor is singularly focused on bringing back New York City’s economy, now that coronavirus cases have dropped.

Mayor Eric Adams has made no secret of his desire to fast-track New York City’s recovery from the coronavirus, and in his regular briefings with health officials, he has been encouraged by the latest metrics: Cases have greatly receded while vaccination rates have hit nearly 90 percent for adults.

But Mr. Adams wanted input from another key sector.

Earlier this month, the mayor entertained a dozen business leaders at his official residence, Gracie Mansion. Over vegan mushroom couscous and wine, Mr. Adams asked what it would take to get people back to offices, according to several participants. The leaders talked about the difficulty of persuading workers to return five days a week — and whether three days was more realistic — and the importance of making the subway safe.

The mayor and his team left the event with a to-do list, including creating a marketing campaign to highlight the city’s comeback.

If the get-together at Gracie Mansion seemed unusual, that’s because it was: Most of the business leaders had never been inside the mayoral residence.

Mr. Adams, a Democrat, has had regular conversations with some of the city’s most influential business leaders, including David Solomon, chief executive at the banking firm Goldman Sachs, and Jonathan Gray, president of the private equity firm Blackstone, to seek their advice — a stark contrast to Mr. Adams’s predecessor, Bill de Blasio, who had a fraught relationship with the business community.

The meetings have underscored not just Mr. Adams’s focus on reopening the city, whose economy has been devastated by the pandemic and is only now slowly rebounding toward health, but also his determination to work with the city’s business leaders in making it happen.

Since taking office in January, Mr. Adams, a former police captain, has had to respond to a series of high-profile crimes, including the shooting deaths of two police officers and violent attacks against Asian Americans. That continued last weekend, with the stabbing of two workers at the Museum of Modern Art, the death of an 87-year-old vocal coach who was shoved to the ground on a Chelsea sidewalk and the disclosure that a gunman targeted homeless men in the streets of Lower Manhattan and Washington, D.C.

But in recent weeks, Mr. Adams — who had made addressing crime a central theme of his mayoral bid — has also begun emphasizing another core campaign message: New York needs to return to normal, and the mayor believes that time is now.

The mayor recently ended the mask mandate in schools and lifted proof-of-vaccination requirements for indoor activities. He has crisscrossed the city to convey the importance for the city to shed its pandemic way of life, making it a point to be seen at high-profile events like ringing the opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange and attending Fashion Week with Anna Wintour. He has even adopted a scolding tone toward those who are reluctant to return to the bustling streets of Manhattan.

“You can’t stay home in your pajamas all day,” Mr. Adams said at an event to announce his economic development team. “That is not who we are as a city. You need to be out cross-pollinating ideas, interacting with humans.”

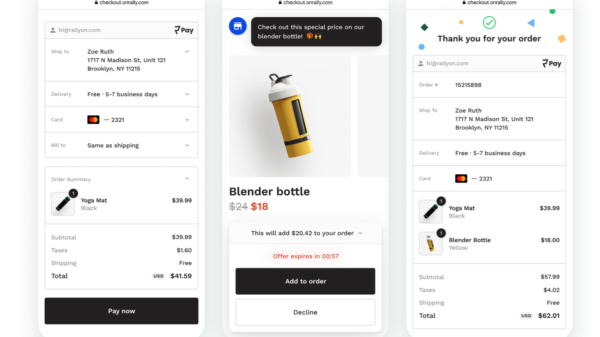

The city’s financial challenges are harrowing: The unemployment rate has remained high at about 7.5 percent, roughly double the national average; office vacancy rates rose to 20 percent, the highest level in four decades; tourism is not expected to recover until 2025; the city’s budget relies on billions of dollars in federal aid that won’t last forever.

Last week, Mr. Adams released a 59-page “blueprint” for the city’s recovery that focused on reducing gun violence, removing homeless people from the subway and making outdoor dining permanent — reflecting the guidance of business leaders.

“Job No. 1: You have to address the safety issue,” said Charles Phillips, the founder of a private-equity firm who organized the Gracie Mansion event. “The mayor understands that obviously, with his background. You have to make the city appealing from a safety standpoint.”

The business leaders told the mayor that the timing of New York City’s recovery was urgent.

“We just had our best week since Covid began in 2020 — occupancy last week was over 30 percent,” said Scott Rechler, chairman and chief executive of RXR Realty, a major commercial real estate firm and another adviser to the mayor. “That’s not a number I’m thrilled with — it’s usually in the 90s — but every CEO and head of H.R. has a plan in place to bring people back in the next 60 to 90 days.”

Two years into the pandemic, the city’s economy faces numerous challenges. With many employers expected to adopt a hybrid approach where workers would come in three days a week, sales tax revenue is expected to drop by $111 million a year. The occupancy rate for hotels, which had plunged as low as 40 percent in January when the Omicron variant hit, was at 67 percent in mid-March, according to STR, a hospitality analytics company.

Subway ridership is at about 60 percent of its prepandemic levels, and transit leaders have suggested that they can no longer rely heavily on fares to fund the system. On Broadway, just 20 shows are running at 41 houses, though attendance has been around 85 percent, and many more shows are expected to open by the end of April.

Mary Ann Tighe, chief executive of the real estate firm CBRE for the New York region, said she had spoken with Mr. Adams several times since he took office, and has told him that it was important to make people feel comfortable returning.

“It’s about getting the basics right,” she said. “People will come back to a city that they feel safe in and that is clean, and those two conditions allow the city to do much of what it does organically — make great art, make great food, make great business deals.”

In Mr. de Blasio’s final days as mayor, he continued to deliver near daily news briefings on the virus that consumed his last two years in office, claiming 40,000 lives in New York City.

Mr. Adams did not continue the practice. He regularly takes questions from journalists, but his last news conference dedicated to the virus and the city’s health care system — and not focused on relaxing restrictions or on economic recovery — was on Feb. 11 at a health center in Brooklyn, the same day he announced a $100 incentive for people who receive a booster shot.

He has not discussed the growing concerns in recent days over the BA.2 subvariant that is fueling a rise in cases in the United Kingdom. Instead, the mayor seems devoted to delivering a different message.

At a recent event in Times Square, Mr. Adams approached random pedestrians in search of a tourist. Finding one from Canada, he delivered a simple message: “Spend money.”

Three days later, Mr. Adams made the same pitch at the Blue Note jazz club in Greenwich Village: “Some of you are from out of town, and I have one request of you: Spend money.”

Beyond being the city’s cheerleader, Mr. Adams has also embraced the role of city psychologist, encouraging New Yorkers to move past the trauma of the pandemic and to stop “wallowing.” Mr. Adams said that removing masks in schools was an important step.

“The return to normalcy is about substantive things we have to do and symbolic things,” Mr. Adams said in an interview. “As much as we say things are normal, the face mask is a symbol that things are not. It’s time to see our faces again, particularly our children.”

Some elected officials were alarmed by Mr. Adams’s decision to remove masks at schools, pointing to low vaccination rates among some children. They also took issue with lifting the proof-of-vaccination requirement for restaurants, movie theaters and other indoor activities, arguing that the mandate made diners feel safer.

“I am worried that this is going to be interpreted as the pandemic is over, and that people are really just going to let their guard down,” said Mark Levine, the Manhattan borough president, a Democrat.

But even as Mr. Adams has lifted some pandemic rules, he has also kept vaccine mandates for municipal workers and for employees of private companies who are working in person. The mayor’s health advisers insisted that those mandates be preserved and were comfortable relaxing the other rules once transmission fell to levels that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers low, according to a person familiar with the discussions.

Mr. Adams said he kept the employer mandates because people spend more time in workplaces and have a longer risk of exposure over an eight-hour workday.

“The doctors feel strongly that that’s where the most susceptibility is in terms of passing on Covid,” he said in the interview.

Mr. Adams has also acknowledged that workers might not return to offices five days a week. He said he is open to converting office buildings in Midtown Manhattan to housing, and after visiting an office with water views recently, he mused, “I could put my kitchen here; I’d love to live here.”

Some critics, including Joseph Borelli, the Republican minority leader in the City Council who recently dined with Mr. Adams at Angelina’s restaurant in Staten Island, want the mayor to end the private sector mandates.

“They’re a barrier for those who may want to return to work in New York,” Mr. Borelli said, adding that a friend who was unvaccinated and worked in finance was working from an office in New Jersey to avoid complying with the city mandate.

Similar criticism has mounted over the status of another unvaccinated New York employee: Kyrie Irving, the Brooklyn Nets’ star point guard who is barred from playing in New York City. Mr. Irving’s teammate, Kevin Durant, suggested that Mr. Adams was “looking for attention”; LeBron James wrote on Twitter that banning Irving “makes absolutely zero sense,” adding the hashtag #FreeKyrie.

Mr. Adams suggested a simple solution.

“Kyrie can play tomorrow,” the mayor said at a recent news conference. “Get vaccinated.”

Sharon Otterman contributed reporting.

Advertisement