Historic building that houses the Galerías Pacífico shopping mall welcomes back the CCB, this time with a federal agenda.

Hannah Gonzalez is a student journalist from Ithaca, New York, United States. Currently studying Journalism with minors in Spanish and Portuguese at Northwestern University, she enjoys writing about music, arts and culture.

From the indoor balcony of the Centro Cultural Borges (“Borges Cultural Centre,” CCB) in Buenos Aires, one can see and experience culture, history and commerce all at once.

Below is the luxurious Galerías Pacífico shopping mall; nearby are the iconic murals depicting various scenes of family, nature and other sociocultural values. Artistic exhibits surround this midpoint on all sides, creating a meeting place where these three elements intersect.

The Centro Cultural Borges, bearing the name of Argentina’s most famous writer, reopened its doors this March after a two-year pandemic closure, this time in state hands.

The space is replete with 13 exhibition spaces, three performance halls and a small open library. The Parisian-style building, constructed in 1891, has long been recognised as a cultural meeting point — it was originally the first home of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes.

Under its new management, the four pavilions of the Centro Cultural Borges currently feature the Bon Marché hall of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes and a sprawling exhibit dedicated to legendary folk singer Mercedes Sosa, as well as multiple rotating tango and jazz concerts.

It also proudly displays multiple inaugural exhibitions as well as two exhibits that opened on May 11; one dedicated to the late Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes, and another by Diana Schufer, Las palabras se las lleva el viento (“Words are carried by the wind”), presented in dialogue with the works of the legendary writer for whom the Centre is named: the incomparable Jorge Luis Borges.

During former president Carlos Menem’s administration (1989-1999), the historic building passed from the hands of Ferrocarriles Argentinos to hotel businessman Mario Falak for the purposes of creating the Galerías Pacífico shopping centre, according to . Part of the building was allocated to the Borges Cultural Centre, which, starting in 1995, was managed by the private Fundación para las Artes (“Foundation for the Arts”).

The group remained in charge of the Centre until its closure due to the pandemic, after which the National Culture Ministry recovered the space in early 2021, following negotiations between the two parties.

Ezequiel Grimson, former undersecretary of cultural policies for Buenos Aires Province and ex-culture director of the National Library, is the CCB’s new director.

“The Centro Cultural Borges had gone through some rather difficult last few years in its private management, and the arrival of the pandemic made it impossible for the project to continue,” he told the Times in an interview.

“The National Culture Ministry took charge [of the Centre] on the basis of an agreement that was made between the Fundación para las Artes and the National Culture Ministry,” he explained. After the changing of hands, Grimson and his team worked “for practically an entire year on its architectural transformation.”

According to a sharply critical published by Infobae in August 2021, the process did not go quite so smoothly. Penned by Blanca Maria Monzón, the CCB’s director of the Audiovisual Department before the change in management, the article voiced complaints that not all employees were able to keep their jobs.

“During the pandemic, the Fundación para las Artes informed the staff of the Borges Cultural Centre that they had to transfer to the Culture Ministry, since the Fundación could not continue to absorb their salaries,” writes Monzón.

“The situation of the monotributistas [self-employed staff] — some with years, and decades, of sustained.

permanence in the institution — was much more uncertain. They promised that the Fundación would remain an appendage within the CCB, and would therefore continue to assume the commitment to pay their salaries: no-one would be left without work.”

“I found this argument dubious,” the article continues. “Since its inception — and for 26 uninterrupted years — the institution never enjoyed sufficient funds to place all its workers on permanent staff, particularly the hierarchical personnel. Unfortunately, time proved me right. A few days later, they told us: we have no more money, turn to the State.”

La Nación reported in March that the Culture Ministry absorbed about 20 employees from the Fundación para las Artes.

Monzón could not be immediately reached to comment on this issue.

Despite the complaints, many experts are supportive of the changing of hands, as well as the role of the state in this particular project.

Sebastián Hernaiz is an author and professor of Literature at the University of Buenos Aires. Though he had not yet visited the newly reopened CCB, he believes that the state has a responsibility to participate in such projects.

“Undoubtedly, it seems important to me — and it is part of their duties — that state institutions can participate in the preservation and dissemination of our cultural heritage,” Hernaiz told the Times via email.

“I understand that the management of the Cultural Centre, in the hands of the Culture Ministry, proposes to do so with the space dedicated to Borges in a way that the previous management did not have among its priorities,” he continued.

Victoria Verlichak, art critic and culture reporter for Noticias magazine, feels similarly about the role of the state.

“The state must participate in culture,” said Verlichak, who covered not only the Centre’s reopening this year but also its initial opening in 1995. “It cannot remain in private hands alone, although private participation is also essential.”

Looking up, one can see the murals on the dome of the shopping centre painted by artists Antonio Berni, Juan Carlos Castagnino, Manuel Colmeiro, Lino Enea Spilimbergo and Demetrio Urruchúa in 1946. They depict varying scenes and situations, representing “the primary values and socio-cultural practices common to diverse cultures,” according to the Galerías Pacífico.

Though patrons can be seen perusing exhibits at the CCB while toting bags from Levis, and a Starbucks can be found mere metres from the second floor entrance, other more commercial elements of the mall have collided with the cultural and the artistic to produce a thoroughly unique identity. A portrait of Frida Kahlo hangs in the window of the Swatch store alongside a display of colourful watches from the company’s art-inspired collection, produced in collaboration with — fittingly enough — French cultural centre Centre Pompidou.

At every turn shoppers can find a display of photography, visual or textile art. Some exhibits can be explored on foot, others are protected behind glass cases.

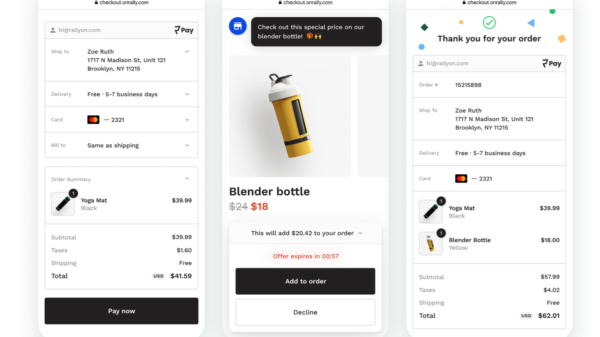

There is even a shop within the Borges Culture Centre, rounding out the commercial connection. The Mercado de Artesanías Tradicionales e Innovadores Argentinas (“Market of Traditional Artisans and Argentine Innovators,” MATRIA) store hosts a monthly rotating exhibition of work by artisans from all over Argentina, underlying the federalist slant of the space.

“The federal mission is also carried out through the store of artisans, which presents productions that otherwise could not be seen in our federal capital,” Grimson told the Times.

Commercial aspects aside, the Centre also currently features a collaborative drawing exhibit, a workshop display in tribute to Italian-Argentine artist Libero Badii, and multiple photographic exhibitions.

Juan Pablo Spicer-Escalante, a professor of Hispanic Studies, professional photographer and patron of the CCB, had visited the space many times before its closure in 2020. Standing in front of the Ayni photography exhibit, he told the Times that the space’s features and exhibitions are “remarkable.”

“For me, it has now become a much more cultural centre,” the 58-year-old professor stated. “What they have here seems to me to be really exceptional,” he continued. “I had not seen this before.”

Hernaiz, who teaches private courses dedicated to Jorge Luis Borges’ works as well as classes on Argentine literature at UBA, highlighted the author’s role in contemporary Buenos Aires and the importance of accessibility to his extensive work.

“I think it is important to have exhibitions, workshops, reading spaces, reading circles,” the 40-year-old said of what a cultural space such as this should offer. He emphasised the importance of bringing Borges’s work closer to readers who “have not yet found the entry point.”

For Spicer-Escalante — who grew up between Argentina and the United States and currently teaches at Utah State University — the newly renovated space summons people to do just that.

“It invites a person to come and visit much more than before,” he said. “To me it was a nice, but cold space before, and this seems much more natural.”

In terms of public response, Grimson says the Centre is satisfied with the number of patrons passing through and the attendance at shows alike.

“We are very pleased,” he said, assessing the public response to the reopening. “Around 5,000 people are coming each week, the shows in general have a full house.”

The director, highlighting the federal mission of the site, also emphasised “representation from all corners of our country, through diverse expressions,” ranging from visual exhibitions with artists and photographers from diverse places in the country, to the artisan store, to the free beginner’s tango classes offered on weekends.

“In that way we are seeking, finding and receiving different proposals and projects that put us in an interesting creative dialogue with diverse communities,” concluded the director.

All in all, the space encompasses an important cultural plurality that is characteristic of Borges’ work — everything that was and is Argentina.

For Spicer-Escalante, who met Borges in Buenos Aires in 1984, the space ultimately embodies the legendary author as a person.